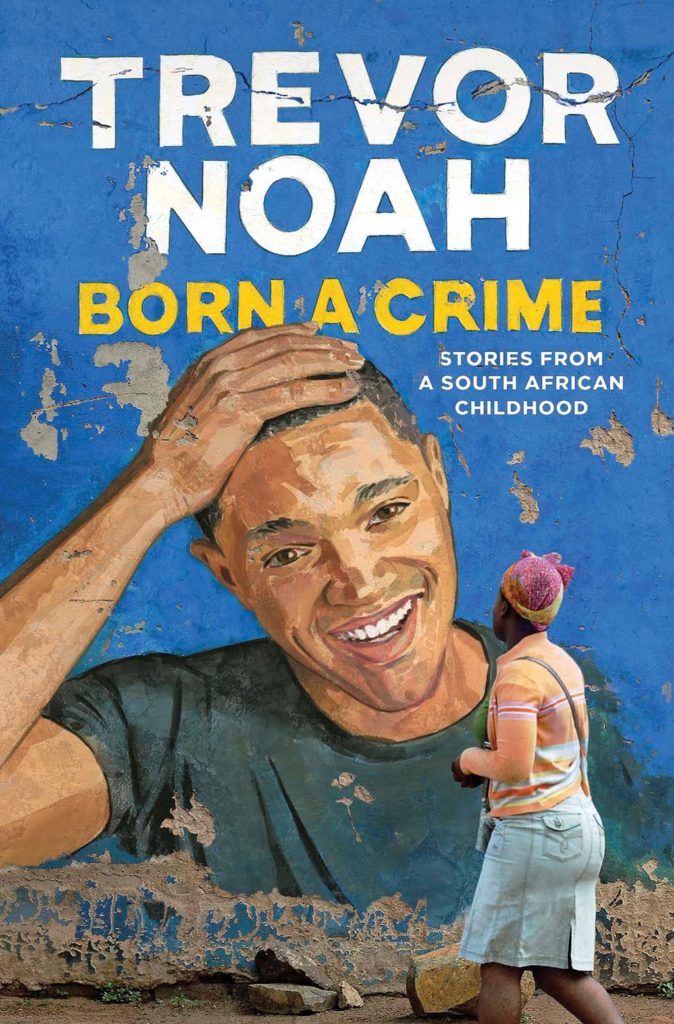

Recently my son introduced me to the serious and comedic work of Trevor Noah. In particular, he suggested I read a passage from Trevor’s autobiography, Born A Crime, in which Noah describes his experience as a bi-racial child growing up in South Africa while apartheid was still the rule of law. In it Trevor recalls how when he was ten years old his father (who was white, and could not openly be with Trevor or his black mother) disappeared from his life. By then, his mother was remarried to an angry, jealous man; in reference to that period of his life, he says “We’d gone from living under apartheid to living under another kind of tyranny, that of an abusive, alcoholic man.”

Despite his challenging home-life, Trevor succeeded in school and had a meteoric rise as a stand-up comedian. However, his personal success wasn’t able to keep at bay persistent nagging thoughts, and he wondered where his dad was, if he thought about him or what he did, and whether he was proud of him. He observes that “When a parent is absent, you’re left in the lurch of not knowing, and it’s so easy to fill that space with negative thoughts.

Trevor says his saving grace was his mother’s refusal to support his own negative paradigm. In fact quite to the contrary, she extolled the best of his father. Clearly, she understood how important it was for Trevor to incorporate into himself his father’s best reflection. So when she spoke to him she often reminded him that he was good with money, like his dad, and when he smiled she would tell him his smile was just like his dad’s. Most importantly she let Trevor know that his father had made an active choice to be his father, and that his absence was due to circumstances (apartheid and then a violent step-father), and not a lack of love or disinterest.

At twenty-four years old and with his mother’s help he decided to search for his dad. With no address, and a seriously private father, finding him was no small task. When Trevor tried to track him down through the Swiss Embassy, he got the runaround. They summed it up to him by saying: “We’re the Swiss embassy. Do you know nothing about the Swiss? Discretion is kind of our thing.” Nonetheless, he persisted. And he succeeded.

Once Trevor reconnected with his father, he was overcome with emotion, and an insatiable desire to “know” his father. And his father was immediately transported back in time to when Trevor was ten years old: He offered him Sprite, custard with caramel and the Potato Rösti that he knew Trevor loved to eat.

Trevor tried to interrogate his father for information (having so much to catch up on), but answering questions wasn’t his father’s style, and he stonewalled Trevor at every turn. Instead his father brought out an oversized photo album filled with clippings of everything Trevor had ever done, every time his name was mentioned in a newspaper, everything from magazine covers to tiny club listings, from the beginning of his career all the way through to that week. “For years I’d had so many questions. Is he thinking about me? Does he know what I’m doing? Is he proud of me? But he’d been with me the whole time. He’d always been proud of me…He was never not my father.”

What does it mean for a child to know a parent? What does it mean to a child to be known by a parent? Is it about acts and facts? About a common experience and ultimately a shared history? About a feeling? About trust? Or some combination or parts of all of these things? How do hearts and minds and souls connect? It seems to me that these are basic, primal needs we all have, and yet the questions have no exact, quantifiable answers.

What does seem irrefutable is that every child needs to know that she is championed and loved. Being present can make that a simpler task but there are ways to be known even in one’s absence. What co-parents say and do to support one another is not just about paying lip service to the idea of co-parenting. Words will leave indelible marks. And those marks will be translated into a child’s sense of self. Whether the words used will be brushstrokes of compassion and love, or anger and betrayal is well within the means and control of parents. And in that regard all children deserve nothing less than their parents’ best efforts.