For as long as I can remember, the power of language has fascinated me: which words we choose to express our thoughts, the tone we use when speaking, and–once they’re out–the impact they have on others. When a couple that had once been in love is no longer in love, or at least one of them is not, this is particularly powerful. And how those words translate to children speak volumes.

In discussions with divorcing clients who have children, I often talk with them about the importance of being together when they tell their children that they plan to divorce, and in doing so emphasizing that they, the children, are not responsible for the divorce. We talk about how important it is for children to hear that their parents will never stop loving them; that their love for them is boundless and will endure.

However, kids are astute. They often wonder (and sometimes ask) “if you could stop loving each other, why should I believe you when you tell me you’ll never stop loving me”? Parents, of course, try to assure their children that this could never happen, but they are often at a loss to “find the right words”. It seems to me that we need more intentional language. If love is a word we use to express a broad range of feelings and actions, perhaps it’s not surprising that kids find it tricky to distill the “why” behind how you can stop loving a spouse while simultaneously guaranteeing that you will never stop loving them.

As I thought about this idea, I began to think about the many words for snow that the Inuit have. Their landscape and their lifestyle demand language which clearly expresses “snow” for all occasions: there’s a difference between “softly falling snow” (aqulokoq) and “the snow that is good for driving a sled” (piegnartoq), and knowing which one is outside your door matters.

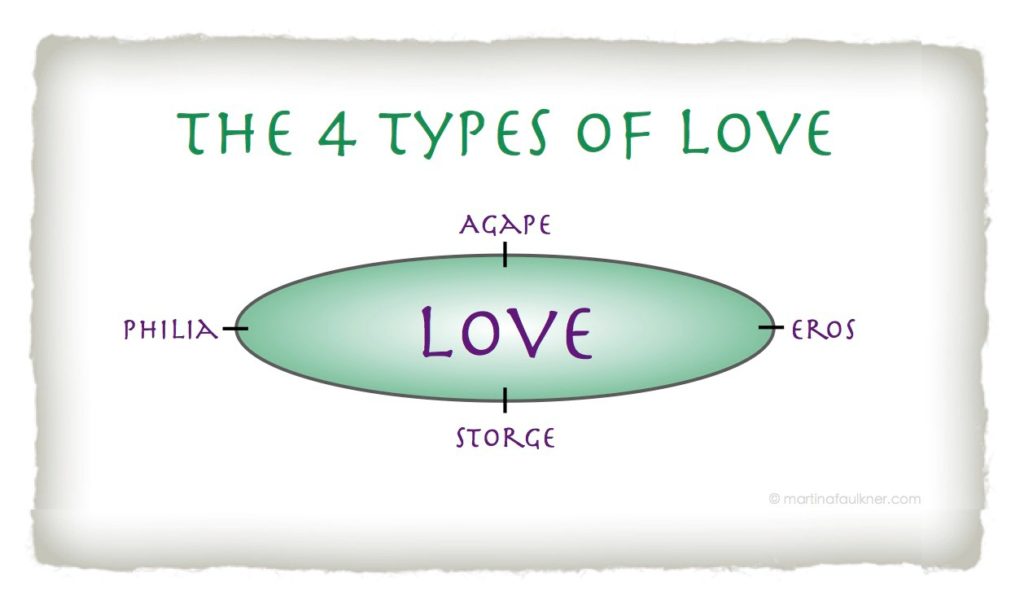

Ancient Greek has at least four different words for love: agápe, éros, philía, and storgē. Understanding and adding those words to the lexicon of divorce, and using them in the course of restructuring families, could add nuance and speak truth to an evolving family. Terms like ‘physical custody’, ‘legal custody’, and ‘shared custody’ connote images more linked with property than children; what if, instead of using those words when talking to and about restructured families, we used loving words to describe reconstituted relationships between former spouses, co-parents and their children?

What if we talked about those Ancient Greek words describing kinds of love with intentionality? So that when we talked of éros-love, we understood it to mean love in a passionate, intimate, sexual sense (the goal of éros has been described as transcendence and the means to get there as being intimacy and beauty), and when we talked of agápe-love, we understood it to mean brotherly love, or charity; when talking of philía-love we would understand it to be affectionate regard, or friendship, loyalty to friends, family, and community, and storgē-love would evoke love and affection, especially of parents and children.

If this language were to become part of our lexicon, then perhaps when parents and children had that difficult initial conversation about divorce, they could talk to their children about their everlasting storgē-love for them, and their philía-love for one another and their restructured family. They could talk about the complexity, and adult nature of éros-love, and how although that aspect of their relationship had changed, they would forever be a family filled with philía-love. Depending upon their children’s readiness, they could also talk about their hope to continue sharing their agápe-love with their community, and show that intention by creating a shared charitable goal or project together.

Although some people might suggest this shift in reclaiming parts of an ancient language is an unrealistic goal, we might do well to remember that it wasn’t long ago when words like “upload”, “selfies”, and “tweet” weren’t common parlance either.

We create language to express the ideas, people and things we value. What could we possibly value more than telling children that their parents’ love for them is enduring? It is storgē, and their family’s love is everlasting: it is philía.