It gives me great pleasure that my son agreed to gift me a guest blog. Adam’s been my writing mentor, and gently broke me of my legalistic writing tendencies to hopefully become that of a more natural storyteller.

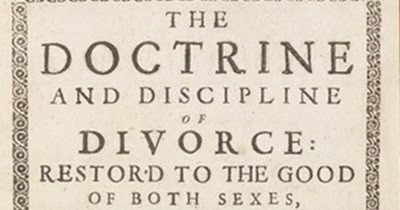

Prior to Adam’s departure for the West Coast to attend graduate school, he ran across the fact that John Milton wrote a treatise on divorce way back in 1644; he’s an inveterate reader, and told me he was drawn to that particular treatise because of the nature of my work—somewhat in the vein of buying a red car and then seeing only other red cars on the road.

We got to talking about the treatise, and Adam’s fascination with the fact that four hundred years ago, John Milton (whose name may ring a bell as the author of Paradise Lost), seemed so ahead of his time in both analyzing his own unhappy marriage, and so forwardly proposing several arguments for divorce which were then quite radical. I have found both Milton’s and Adam’s perspectives to be illuminating and hope you will too.

Note Bene: Adam has chosen to leave intact all of Milton’s unconventional and/or period spellings.

By Adam Singer

At some point I ran across the tidbit that John Milton wrote not one, not two, but four treatises on Divorce. I immediately thought that perhaps I could find some good material for my mother to use in a blog; needless to say, she assigned that task to me, and I’ve now written up my thoughts and observations and tried to contextualize them through history.

IN 1642: The English Civil War (that thing with Oliver Cromwell, which you may remember from high-school history) began. Milton was a supporter of the Roundheads, while his wife’s family were Royalists. Wikipedia posits that this divide was a factor in their separation shortly after marrying.

Living with other people can be like sharing a red car on a roadtrip. The things which matter to the people we love begin to matter to us.

In reading John Milton’s 1643 treatise, it struck me as remarkable that the foundation of his argument was the need to legitimize divorce on the grounds of spousal incompatibility.

In order to give context to the times, I’d like to point out that in 1643, the same year John Milton began his treatise on divorce, Louis XIV (age 5) succeeded his father as King of France. He reigned for an all-time-record-breaking 72 years.

Since Milton’s Almighty argument comes from Chapter 2 of Genesis, I’m starting there.

In that chapter, God says that “It is not good that Man should be alone; I will make an helpmeet for him.” Milton reasons that God’s intent was for people entering into a marriage to form mutually-beneficial partnerships. “A meet and happy conversation is the chiefest and the noblest end of mariage* ”, Milton argues—carnall knowledge is far less important than the purpose a marriage serves in “preventi[ng]…loneliness to the mind and spirit of men.”

Without mutuality of mind, marriage cannot survive the random hardships Life sometimes throws at us. We are (ideally) looking for a partner to weather storms, not just to fulfill the “impatience of a sensuall desire.”

If the “sobrest and best govern’d man….too eager to light the nuptiall torch” of Chapter III was drawn from personal experience, Milton was suffering from some serious buyer’s (please excuse the phrase, in this context) remorse. His lament that “for a modest error a man should forfeit so great a happines, and no charitable means to release him” could only have been inspired by an extraordinarily mismatched marriage.

It seems that—at a blunt guess—he married a gorgeous girl with nothing in her head. His arguments which rest on flaws of character, rather than the Canon Law’s ignorance of the Mercy Of Moses (his phrase), always involve a man locked into a marriage with a woman who (my guess, again) resents his intellectualism, and who in turn he cannot respect as an intellectual equal.

At the time of this treatise’s publication, he had been shackled to Marie Powell for three (of an eventual ten) mutually-miserable years. His plea for “Mosaick mercy” is a desperate one indeed.

Twenty-eight years later….

IN 1670: Lord John Manners obtains a special Act Of Parliament allowing him to divorce his wife (whom he’d previously separated from on grounds of adultery). Among attendants to the proceedings was King Charles II, who found the debates “as good as a play”.

During these proceedings, Milton went to battle on behalf of beleaguered spouses the world over, trapped in nightmare couplings and toxic marriages. The wording is always from a man’s perspective, and in numerous instances points to his absolute hateful incompatibility with his first wife (“…sometimes continuance in mariage may be evidently the shortening or endangering of life to either party”). His in-absentia portrait of his wife, honestly, is why I’d consider this a literary masterpiece as well as a legal one.

“Please dear GOD,” you can hear him crying between the broad lines of this treatise, “repeal or change the Canon Law.” That was the ecclesiastical law (originating in the Vatican) which forbade divorce. He says many times, and eloquently, that the Canon Law is an offense to God’s intent that we find happiness on Earth.

It wasn’t until 1857, 113 years after Milton wrote his treatise that The Matrimonial Causes Act was passed by a specific Act of the British Parliament, therein making divorce available to a wider population.

Milton aimed to prove the necessity of divorce beyond any objection “either from Scripture or light of reason”, and did so not only with the bombasticism of published work in those days, but sometimes the urgency of a man pushed to the edge of sanity by a woman who despises him just as much as he loathes her.

The word ‘conversation’ appears several times, always with the greatest emphasis placed upon it. This, I believe, is the crux of the aforementioned ‘light of reason’—that a marriage ought not be counted as valid if there is no mutual mentality between its partners.

In general phrases, Milton implies a sharp criticism of a legal system which lacks mercy. But in so ardently arguing for conversation, he appeals as well to our common sense. Surely, God did not intend marriage as a means to punish us—but to lend structure to our lives, in having a partner and helper to weather the random hardships of life.

And speaking of random hardships…..

Most marriage vows include some variant of the promise to “love her/him, comfort her/him, honor, and keep her/him in sickness and in health”. Milton acerbically tackles that assumption in this essay as well, with the following mockery of what were clearly the standard mariage-vowes of the day:

….if any two be but once handed [‘joining hands’; saying “I do”.] in the Church, and have tasted in any sort the nuptiall bed, let them finde themselves never so mistak’n in their dispositions through any error, concealment, or misadventure, that through their different tempers, thoughts, and constitutions, they can neither be to one another a remedy against lonelines, nor live in any union or contentment all their dayes, yet they shall, so they be but found suitably weapon’d to the least possibility of sensuall enjoyment, be made, spight of antipathy to fadge together, and combine as they may to their unspeakable wearisomnes and despaire of all sociable delight in the ordinance which God establisht to that very end.

This ridicule of the idea that a married couple can rely upon each other in hard times, being a comfort and a friend, et cetera, clearly comes from his own horribly mismatched partnership. In so, so, SO many ways, he is pointing out how a marriage can fail, and he does it with brilliant comedic flourishes like this throughout.

The absolute necessity of a good conversation in a successful relationship, over and over again, is the theme Milton introduces and expounds upon. He sings it from the rooftops, and howls in dismay at the pigheadedness of this system locking him into a hateful partnership.

The next aspect of this treatise which must be addressed is, by my eye, the most radical of the whole twenty-page document.

In Chapter III, Milton points out that “[Canon Law has made] such carefull provision against the impediment of carnall performance,… [but none for] unconversing inability of mind.” There is that idea again! — the absolute necessity of good communication between spouses.

In modern parlance, what he’s describing (here and elsewhere) might fall under the heading of ‘irreconcilable differences’. But what makes the above quote stand out is the implicit criticism of the consideration that a marriage is not valid unless it is consummated. He is arguing that, if sexual dissatisfaction is cause for divorce, than mental dissatisfaction ought to be given the same priority. If there is no intellectual/communicative compatibility between people, they cannot possibly sustain a marriage or a family together.

This is a startling statement, and (once again) its existence at ALL, much less in the frank terms set forth in this document, in the year 1644……is remarkable. In a world where divorce was unacceptable, his dogged insistence that “love in mariage cannot live nor subsist unlesse it be mutual” is astounding.

Without the ability to converse pleasantly with your spouse, says Milton, marriage would be a miserable partnership. A friend of mine recently described his relationship as being like “having a sleepover with your best friend when you were a kid, but all the time.” If that ain’t a perfect example of what Milton wanted but desperately lacked, I don’t know what is.

IN the 1620s-40s: Puritan families begin their Great Migration (approx. 20,000 immigrants over the course of those two decades) from England to America, establishing the Massachusetts Bay Colony and deeply influencing the culture of New England; our entrenched societal perspectives on divorce did not escape this influence.

I find the fact that Milton wrote this treatise in 1644 to be astounding not only for its prescient attitude, but also for its surprising readability. Unlike Paradise Lost, this isn’t epic poetry in meter, but simple, emphatic English.

The oddest phrase he uses, I think, isn’t one unfamiliar to modern ears—but rather a weirdly contemporary one: ‘a single life’.

#SingleLife is, according to urbandictionary.com:

-

A term commonly used by skanks, Expressing love of single life, because they can’t keep a relationship for any longer than a week.

-

Someone that has just emerged from a long-term relationship and is trying to show their ex they’re doing better than them.

Given the context in which it appears, it seems that J.M. was pining for the second of these two. Without Facebook or Instagram, he couldn’t as easily show Marie how much fun he was having with other girls, but I’m sure that the impulse was there.

#MiltonSingleLife

Marriages falter and fracture when there is a failure of communication. Issues like infidelity or abuse are more obvious reasons to separate from an incompatible partner–but if I’ve learned anything about this subject matter from my Mom, it’s that on some level the lack of meaningful communication and conversation undergirds most unhappy relationships.

It is worth noting, as well, that the characters of Adam and Eve in Paradise Lost rely upon each other, and in many ways embody the qualities Milton espoused in this essay twenty-odd years earlier.

In his epic Paradise Lost poem he returns to Genesis and ends with an image of that partnership, in the moment of leaving Eden for the uncertainty of the world beyond the Garden:

“The World was all before them, where to choose

Their place of rest, and Providence their guide:

They hand in hand with wand’ring steps and slow,

Through Eden took their solitary way.”