The following blogpost was written in collaboration with my son, Adam Singer.

Adam is a writer with a curious mind, a great interest in historical and biblical texts, and a savvy social media millennial. I’m grateful for his perspective and his social media help, and confident you’ll enjoy his vantage point.

What’s the difference between a written, binding contract and a wish, a hope, a prayer or a covenant?

Enforceability is the first thing that comes to mind, but it’s also the “who” of a contract and the fact that it must be written by and between people in order to be binding, whereas covenants are not necessarily binding in the eyes of the law and are often made between a person and a spiritual entity… and they seem to also have a sort of magic in them, that people often don’t consider fully.

Contracts, non-disclosure, leases, pre-nuptial, post-nuptial or divorce, all compel the people signing them to behave in certain ways because of the legal agreements they have made and the laws that make them binding. Enforceable and empowering, contracts are actions made visible from words, and they’re documents that shape social interactions today, and have done so for thousands of years.

The marriage ceremony, a speech act (the saying of “I do” in a very specific context) intends to legally bind two people in complex deeply impactful ways, but when those two people make vows to one another they are often not mindful of the third party, the State, that joins in their relationship. In fact, it is the officiant’s affirmation to the State that gives protection to the couple and makes their vows an enforceable contract under a State’s laws.

In most of the world just as a document is required to bind a marriage, a document is required to “un-bind” it as well. That being said, various cultures have created unique traditions, which derive from histories and customs evolved over thousands of years. In the orthodox Jewish tradition, no divorce is complete without a get, or “document of separation”. The document has many similarities to that of a civil Divorce Agreement, but in the religious tradition it is considered crucial because it firmly separates the partnership and acknowledges as much to the community by setting it in writing and making it more tangible.

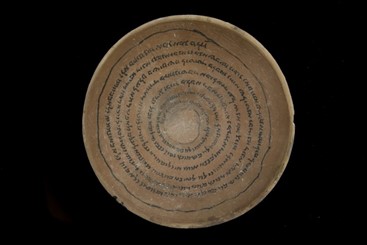

The creation of binding and “unbinding” Agreements between people differs from and has parallels to an esoteric mystical divorce practice that developed during Babylonian times (dating between 500-800 AD), a practice which included the creation of incantation bowls, burying them beneath the doorway of homes, where the purpose was to ward off evil spirits. In Mesopotamian archaeological digs, these artifacts have been discovered beneath the doorways of many homes, and they provide fascinating glimpses into the social conditions and priorities of the people who commissioned these bowls.

There is an enormous amount to be gleaned from studying these artifacts, and interested readers who care to learn more can delve into this linked article for a thorough analysis of the practice and elements of the legalistic language which appear on these objects. One translation in the linked article reads as follows:

This is a divorce writ for the Lilith that curses which I have written for Imi daughter of Qaqi and any name she has. May you be healed, may you be protected, may you be saved…from every evil strong powerful spirit, from active sorcerers, from spells of ZNY the singer prostitute, and the Lilith, and the curse which is killing children that are hers, children of her (female) neighbor. That if you are permitted and have power over yourself (to be with) any person that you may desire, for I have written to you a deed of divorce, a writ of dismissal from this Imi daughter of Qaqi (and) any name that she has…

Harkening back to this article’s earlier comments about Jewish traditions, I’m mindful of the fact that in Jewish homes today, it is traditional to hang a mezuzah on the doorpost of the entrance. The mezuzah is a small box containing a scroll which has biblical language written within it, the Sh’ma prayer, which affirms the Oneness of God. The intention of this practice is to “guard one’s home” against evil spirits, marking the doorway as a barrier to spirits of ill intent.

The connection between the hanging of a mezuzah and the burial of an incantation bowl is fascinating— as can be seen by study of the language used in these artifacts — these are also precious examples of contractual legal language from that era. Some of them (as with the example cited) explicitly call the bowl a “document of divorce” (indicating that the original word is ‘get’, but a translation might say “this [writ of] separation”) for spirits of darkness, forbidding them from entering the home.

Although the specific use of the ‘get’ clearly links this practice to divorce documentation, the nature of these bowls also might be seen as a spiritual parallel to a written restraining order against violent spirits. The mezuzah is a generic descendent of this practice, but these artifacts reveal how seriously people in that era took their protective charms against powers of darkness.

A number of years ago I began crafting AfterMarriage Covenants, explaining to clients that I called them Covenants on account of the fact that they were not enforceable by a Court of law but rather intended to be a statement of shared goals and values between them as co-parents as they moved from being spouses, an affirmation of their new relationship. They state what Divorce Agreements leave out- hopes, intentions, and aspirations. Perhaps they’re a positive spin on incantation bowls…

We hope that everyone reading this stays well in our own dark times and can stay safe from the invisible forces of disease and destruction which are acknowledged in our society today.