The current, wonderful Matisse exhibit at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts includes paintings, cutouts and sculptures of Henri Matisse, and juxtaposes them with many of the objects he loved, and which inspired his work.

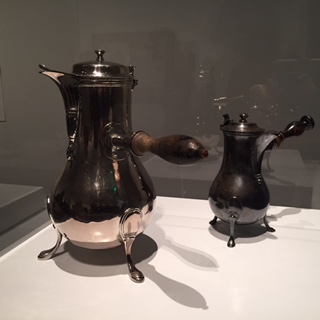

Two silver “chocolate pots”, one given to Henri and his wife, Amélie in 1898, and another smaller pot, which Matisse acquired just after his separation from Amélie in 1939, particularly struck me. The smaller pot is described as a stand-in for the larger one, a near match, it must have elicited emotions associated with an earlier, more innocent time in his life.

In July 1939 Henri and Amélie met for the last time to discuss the details of their legal separation. One of its key provisions was that everything would be divided equally between the couple. The meeting is described as having lasted only thirty minutes, during which time Amélie kept up a flow of small talk while her husband said “My wife never looked at me, but I didn’t take my eyes off her…,” Matisse wrote on the night of that final encounter: “I couldn’t get a word out…. I remained as if carved out of wood, swearing never to be caught that way again.” The description of that encounter made me think about how little they seemed able to discuss the complexities and pain of their relationship. It also made me think more generally about the emotional tie people have to their possessions, what they signify, how Amélie had probably received the larger chocolate pot as a part of their equal division, and how despite some negative associations with their complicated history, Henri sought to replace that pot. Perhaps he found only a smaller version of it; perhaps it felt more fitting that it be smaller as it was intended for him alone. As Henri seemed very intentional about objects and how he used them, it seems more likely to me that he wanted the second pot to be smaller, individual, his alone with the memories he chose to keep with, by and in it.

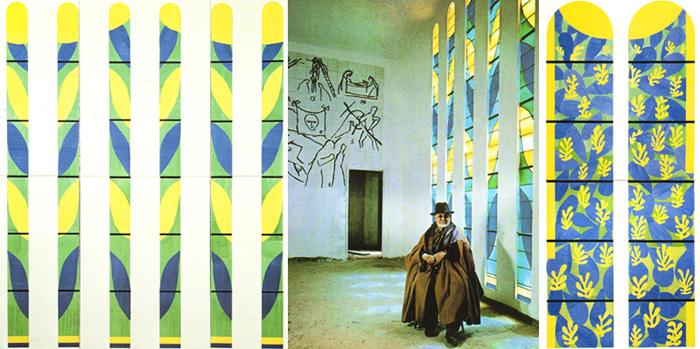

In stark contrast to the small chocolate pot, is the monumental four-year project of designing the interior, the glass windows and the decorations of the Chapelle du Rosaire in Vence, France, the result of his close friendship with Sister Jacques-Marie, who had cared for him when she was a student nurse and he was recovering from intestinal cancer. The symbols and artistry in that church are remarkable, perhaps testament to an unencumbered sort of love. The church seems to me to have been his personal canvas, a culmination of his life’s work, a timeless tribute.

The emotional intensity of the chocolate pot and the Chapelle du Rosaire are palpable- one so small, and one so monumental.

The worth of an object is more than what it could bring on the open market; when trying to reach a marital asset division, recognizing the emotional value objects carry will help achieve peace as well as equality.